Episode Description

This episode explores how Shazia Anwar helps Darlen Wagenius and her husband, Joe, address challenges in accessing quality long term care services. Shazia talks about her introduction to home care activism through her work with SEIU775. And we look at an innovative policy in Washington state and policy efforts at the national level.

Shazia Anwar

Shazia Anwar has been a professional home care provider for 12 years. She is also an active leader and Executive Board member in her union, SEIU 775. Her aim is to ensure that all care workers are lifted out of poverty, and have improved wages and benefits.

Shazia Anwar has been a professional home care provider for 12 years. She is also an active leader and Executive Board member in her union, SEIU 775. Her aim is to ensure that all care workers are lifted out of poverty, and have improved wages and benefits.

Darlen Wagenius

Darlen Wagenius worked for over 30 years in a variety of professions, and the most recent was in the trucking industry. She currently lives at home, where Shazia Anwar is her caregiver.

Darlen Wagenius worked for over 30 years in a variety of professions, and the most recent was in the trucking industry. She currently lives at home, where Shazia Anwar is her caregiver. Dr. Ben Veghte

Benjamin W. Veghte is Director of the WA Cares Fund, the nation’s first universal long-term care insurance program in Washington State. He is also an MIT CoLab Mel King Community Fellow, as well as a member of the Care Guild, a group of 125 innovators redesigning care for the 21st century, and an expert on German and OECD social policy. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and an MPA from the Harvard Kennedy School. His work focuses on developing policies that improve the economic security of workers and help them balance the responsibilities of work and family caregiving. In 2011-2012, he helped launch the Scholars Strategy Network at Harvard University, an initiative seeking to leverage the expertise of leading progressive scholars around the country to better inform public policy and enhance our democratic process. He directed research and policy at Social Security Works from 2012-2015 and led all policy work at the National Academy of Social Insurance from 2015-2018. From 2018-2020, he led the research portfolio at Caring Across Generations, where he led design of Universal Family Care policy, an integrated program of long-term care, childcare, and paid family and medical leave.

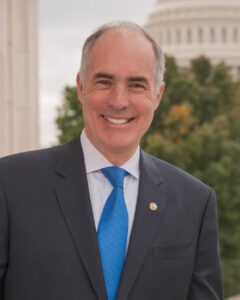

Senator Bob Casey

U.S. Senator Bob Casey fights every day for Pennsylvania families. He is a strong advocate for policies that improve the health care and early learning of children and policies that will raise wages for the middle class. Senator Casey serves on four committees including the Senate Finance Committee, Senate HELP Committee and Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. He is also the Chairman of the Special Committee on Aging, where his agenda is focused on policies that support seniors and individuals with disabilities. Senator Casey and his wife Terese live in Scranton and have four adult daughters.

Sterling Harder

Sterling Harder is President of SEIU 775, a union that represents more than 45,000 nursing home, home care, and residential care workers throughout Washington and Montana. Born and raised in a small town on the Washington coast, Sterling acquired a firsthand perspective regarding the importance of respect, dignity, and justice for workers, given her father’s role as a union mill worker and her mother’s work as a caregiver. Through SEIU 775’s innovative and cutting-edge approach, the Union has demonstrated time after time that workers can and do win standard-setting contracts for caregivers and low-wage workers – including significant wage increases, paid vacation, health benefits, retirement, training opportunities, increased funding for nursing home workers, and the Fight For $15.

Sterling Harder is President of SEIU 775, a union that represents more than 45,000 nursing home, home care, and residential care workers throughout Washington and Montana. Born and raised in a small town on the Washington coast, Sterling acquired a firsthand perspective regarding the importance of respect, dignity, and justice for workers, given her father’s role as a union mill worker and her mother’s work as a caregiver. Through SEIU 775’s innovative and cutting-edge approach, the Union has demonstrated time after time that workers can and do win standard-setting contracts for caregivers and low-wage workers – including significant wage increases, paid vacation, health benefits, retirement, training opportunities, increased funding for nursing home workers, and the Fight For $15.

Blog

Elder Care and Global Care Chains

by Sonya Michel

As the United States population ages, the need for elder care grows, but the number of Americans willing to work in this field cannot keep up with demand. Increasingly, immigrants, both documented and undocumented, are making up the gap. About one quarter of the three million people currently employed as elder-care home health aides in the US are foreign-born—this when the proportion of immigrants in the population overall is only 17 percent.

As the United States population ages, the need for elder care grows, but the number of Americans willing to work in this field cannot keep up with demand. Increasingly, immigrants, both documented and undocumented, are making up the gap. About one quarter of the three million people currently employed as elder-care home health aides in the US are foreign-born—this when the proportion of immigrants in the population overall is only 17 percent.

Such workers participate in what researchers call “global care chains”(GCCs) – in which migrants, primarily women, are drawn from poorer countries to wealthier ones, where they find employment as caregivers for middle-class elders, children and homes. Some migrate out of a desire for adventure or education, but most leave because of unfavorable conditions in their home countries: poverty and a lack of employment opportunities, especially for women; famine or other climate disasters; and violence, either domestic or political. For many, migration means separation from families, including their own children, but they reason that, whatever the emotional cost, they will be able to send back remittances—money that is essential to feed, clothe, house and educate loved ones and enable them to obtain medical attention when needed. But the one thing migrants cannot provide from afar is hands-on care. Thus global care chains serve to transfer “care labor” and resources from poor to rich across the world.

Participation in GCCs varies from one nation to another depending on circumstances at both ends of migration chains. Some sending countries try to prevent women from leaving; Sri Lanka, for example, bars exit for mothers of young children. Others facilitate emigration, recognizing the value of remittances for local economies. The immigration laws of many receiving countries bar entry to potential caregivers, despite obvious need; one is the US, which has no immigration category for such workers, considering them “unskilled” and therefore undesirable. As a result, many of the migrants who manage to enter the US and take care jobs are undocumented and as such, they are vulnerable to exploitation and deportation. A few countries, such as Israel, offer temporary work permits to immigrants willing to provide elder care and even offer them benefits.

Racial and ethnic as well as gender stereotypes reinforce notions of who is qualified for caregiving, deeming some groups “ideal” for this type of work, others “ill-suited.” In fact, not all women, whether migrant or native-born, Black or White, are inherently suited for such a difficult occupation. Individual, not group, characteristics as well as good training are what qualify workers to perform the kinds of tasks, whether routine or specialized, that elders may require. Yet systematic training is not universally available, particularly for migrants, who may also face language barriers. These factors present risks to those being cared for.

Caregiving is highly intimate work, and caregivers’ experiences vary. Many find jobs in private homes, where they have to face the tensions of working and sometimes living in close quarters. “Carees” and their families may be grateful for the help or they may feel uncomfortable having a stranger in their midst, and elders may resist accepting their dependency. Live-in workers have little control over their hours, accommodations, even diets. Many, especially the undocumented, have no benefits—no health insurance and no recourse in case of injuries due to lifting or other workplace stressors.

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of migrant-provided elder care is that the migrants themselves end up with few resources for their own retirement. Indeed, they may spend years, even decades, caring for others while unable to make provision for their own old age. Denied access to pensions such as social security in destination countries, they may return to their countries of origin no longer able to work but needing support themselves. Perhaps by sending a continuous flow of remittances to their families, they have built up social as well as financial capital, but there is no guarantee that they will find a warm welcome in their old homes. Undocumented migrants are often reluctant to make return visits because such travel is expensive, perhaps involving smugglers’ fees on top of regular transportation costs, and may well be dangerous; plus, there is the risk they may not be able to re-enter the receiving country where they have a job. This leads to prolonged absences that disrupt family ties and make it difficult for them to re-integrate. Or they may simply feel uncomfortable in their former surroundings after years of living abroad.

Much of this imbalance can be readily addressed. Worldwide redistribution of wealth would reduce workers’ need to leave their homes in order to earn a living, but that would require reversing centuries of global economic history—something that is unlikely to occur anytime soon. In the meantime, more flexible immigration laws would enable potential careworkers to enter receiving countries legally and return home regularly, thereby maintaining strong ties with their families as well as supporting them financially. Such laws would, ideally, also entitle migrant workers to receive the same benefits, including health care and old-age pensions, that citizen workers enjoy. More training and greater regulation of carework, both institutional and home-based, would benefit carees by improving the quality of care they receive while protecting workers from poor working conditions and other forms of exploitation. Population aging will continue, and with it, the demand for caregivers. As long as global economic inequality persists, global care chains are likely to form to meet this demand. But they need not continue to generate cruel inequities. Wealthy countries must acknowledge their own dependence on migrant caregivers and treat them with the respect and compensation they deserve.

Resources

- The Work that Makes All Other Work Possible: Ai-jen Poo on Why Home Care Workers are Infrastructure Workers, Audio interview, 2021.

- Many of Us Want to Age at Home. But That Option is Fading Fast, Ai-jen Poo and Ilana Berger, NY Times (and reprinted in DNYUZ)

- Most Older Adults are Likely to Need and Use Long-Term Services and Supports Issue Brief, Richard W. Johnson et al, Urban Institute, 2021.

- Setting higher wages for child and home health care workers is long overdue, by Asha Banerjee et al, Economic Policy Institute, 2021.

- Centering Equity in Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer on Financing Models, by Allison Cook and Grant Williams, 2022.

- Fair Pay for Home Care: “an Executive Summary, CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, New York Caring Majority Campaign, 2020.

- The Direct Care Worker Story Project: Collection of direct care worker stories, PHI National

- Immigrant Workers and Care for America’s Elderly. by Kristin Butcher, Kelsey Moran and Tara Watson. 2021.

- The Global Care Tilt: Migrant Caregivers Flock to Wealthy Countries to Meet Rising Demand by Sonya Michel, in New Security Beat, 2019.

- 100th ILO annual Conference decides to bring an estimated 53 to 100 million domestic workers worldwide under the realm of labour standards, International Labour Organization, 2011.

- The Role of Immigrants in Providing Care to the Aging, by Angelica Herrera Venson, DrPH, MPH, 2018.

- Resources:

- Home and Community-based Services in Arizona, California, Delaware, Florida, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, W. Virginia, and Vermont.

- Advancing Action: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Disabilities, and Family Caregivers, by Reinhard, A. Houser, A. et al, 2020.

- The New Medicaid Waivers: Coverage Losses and Higher Costs for States, AARP, 2019.

- Home and Community-based Services Waivers Program Basics

- Home and Community-based Services Waivers in Massachusetts

- Legislation and activism:

- Senator Bob Casey Urges Investment in Home-Based Services for Families, Seniors, and People with Disabilities & Workers, 2022.

- Washington Becomes First State to Approve Publicly Funded Long-Term Care, by Rachel M. Cohen, 2019.

- Direct Care Opportunity Act, sponsored by Chairman Scott, Rep. Wild, Rep. Lee, 2021.

- Fact Sheet, Direct Care Act of 2021

- New Tax Will Help Washington Residents Pay for Long-Term Care, by Ron Lieber, New York Times, 2019.

- New York State Senate Bill S5374, bill to increase home care worker wages, 2021-2022 Legislative Session.